Op 111

A project for the Lincoln Arts Discussion group.

I decided to tackle the final Beethoven sonata this week. I'm a wee bit apprehensive because it's a big ask in four weeks, but it's my turn for our monthly arts appreciation group and I want to share something of value. So Opus 111 it is. To be played at the end of an evening exploring what a piano sonata is.

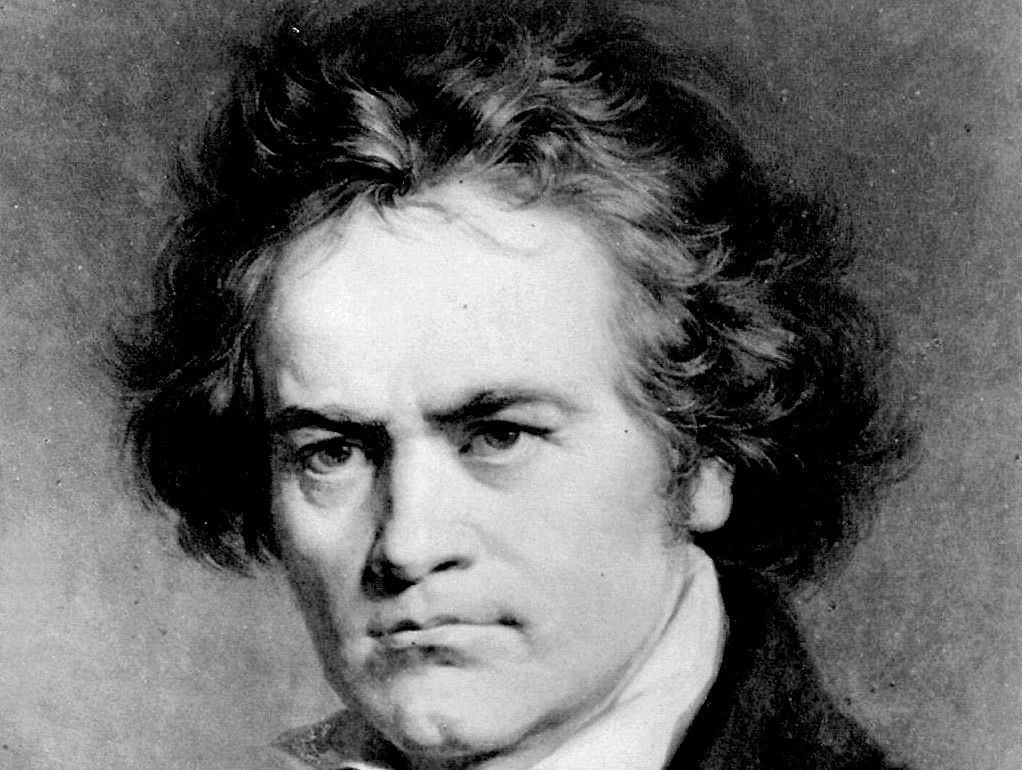

Beethoven's 32 sonatas are the nearest thing to an autobiography that exists in music. Beethoven was never afraid to share his inner life through his music;while some might see this as the tedious working through of a monumental existential angst I find it fascinating .

Ludwig van Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 32 in C minor, Op. 111, composed between 1821 and 1822, serves as his final command to the keyboard. It is a work of radical condensation, stripping away the traditional four-movement sonata structure to leave only two movements: one of stormy earthly struggle and one of celestial transcendence.

I. Maestoso – Allegro con brio ed appassionato

The first movement opens with a jagged, diminished-seventh descent—a "Maestoso" introduction that feels like a heavy door swinging open. What follows is a turbulent C-minor fugue, echoing the "Sturm und Drang" intensity of his earlier Pathétique Sonata. It represents the pinnacle of Beethoven’s dramatic, heroic style: muscular, contrapuntal, and restless.

II. Arietta: Adagio molto semplice e cantabile

The second movement, the Arietta, shifts to C major and enters a realm of pure spirit. It consists of a simple, "holy" theme followed by five variations.

As the variations progress, the rhythmic subdivisions become increasingly dense. By the third variation, the syncopation is so pronounced and energetic that modern listeners often describe it as "proto-jazz." However, the movement eventually dissolves into a shimmering "starry sky" of trills and high-register scales, ending not with a bang, but with a profound, quiet exhale.

Significance in Beethoven’s Output

Op. 111 is more than just a final sonata; it is a philosophical statement. Its significance lies in several key areas:

• The "Final Word": After Op. 111, Beethoven never wrote for the piano sonata again, despite living for five more years. It felt as though he had exhausted the possibilities of the form. When his secretary, Anton Schindler, asked why there was no third movement, Beethoven reportedly replied that he "didn't have time"—though musicologists argue the two movements perfectly represent the duality of "Samsara" (suffering/struggle) and "Nirvana" (peace).

• Formal Innovation: By reducing the sonata to two movements, Beethoven broke centuries of tradition. He proved that a work could achieve "completion" through emotional resolution rather than structural symmetry.

• The Art of the Variation: Along with the Diabelli Variations, Op. 111 redefined the variation form. It wasn't just about decorating a theme; it was about the evolution of the soul through rhythm and texture.

• Literary Legacy: The sonata is famously the subject of a lengthy lecture in Thomas Mann’s novel Doctor Faustus, where the character Wendell Kretzschmar explains why the sonata has no third movement: because the second movement "takes its leave" of the sonata form forever.

It is the end of the sonata as a historical genre... it has fulfilled its destiny and reached its goal." — Thomas Mann, on Op. 111

,